Welcome to the second post in the “Being Black in Iqaluit” series (click for the all the articles). I am really happy that the wonderful Kuthula Matshazi agreed to spend time with me and participate in this series. He has incredible insight, and a lovely story.

Kuthula immigrated to Canada from Zimbabwe in 2001. Fast forward 14 years, and he is now Iqaluit’s first Black city councillor, an advisor with the Government of Nunavut, and an outspoken member of Iqaluit’s ever vibrant community. Here is more about his life and the lessons he’s learned, in his own words.

Tell me about your journey from Zimbabwe to Canada.

We came to Toronto in 2001 and lived in Toronto up to 2009, after I finished my Masters. In 2004, I started school at York, and then I finished my degree in two and a half years, my first degree. Then 2007, I started my Masters and then finished 2008, and then 2009, June, I started working for the City of Kitchener.

Between those gaps, I’ve been a security guard, and I’ve been a marble stone polisher…as well as a plastic moulder. Oh, and also worked at Canada Bread. Oh – this is interesting – when I was a security guard at one of the companies, I got a job as a media relations person. They hired me, and they asked me if I could just stop the security guard job because it wouldn’t really be nice, being a security guard and then during the day I’m a public relations officer. Yeah, I’ve done quite a lot.

I asked councillor @kmatshazi to pick up power tool and pose for a picture. pic.twitter.com/ud6L8yAnO8

— Gideonie Joamie (@tausunni) December 4, 2015

Two thousand seven, eight was really a challenge when I was doing my Masters, because that’s when Yvonne was pregnant. And then I had to juggle school and helping Yvonne, and then after that, when Yvonne had the baby, I had to help her. And it was difficult at that time, because I think from 2005 to 2013, we were living on single income. First, I was at school, and then when I finished school, Yvonne went to school, and then she had a baby, and then she was going to school, and then I came here. In between raising a baby and looking after the family back home, it was difficult.

But on the flip side, sometimes if you work hard, and you’re really focussed, Canada has opportunities for people. It’s really difficult for immigrants to make it, so to speak, but sometimes if you work hard, you do make it. For me, I count all my blessings. I think so far I’ve had it good.

What brought you to Iqaluit?

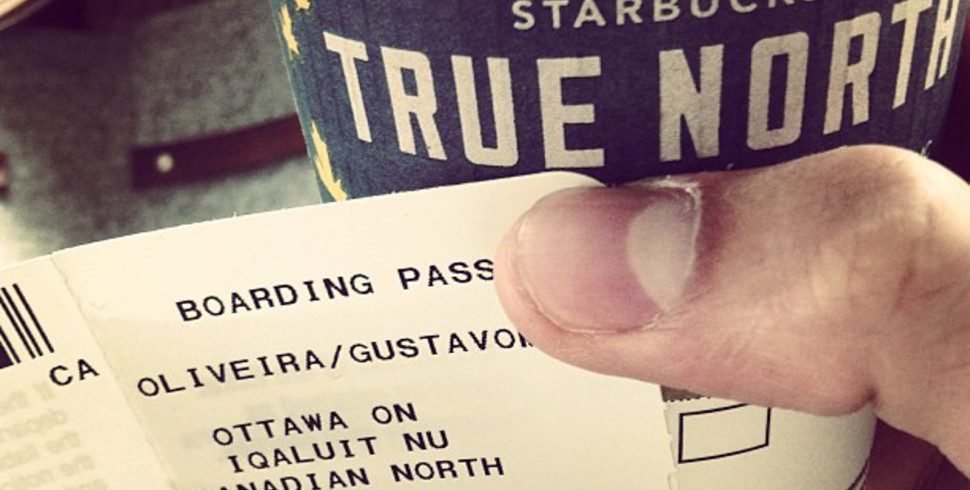

Basically, work. I had a friend of mine who lived here and he asked me if I was interested in coming and working here. But it wasn’t easy when I first came here. I came here first, I think in May, and started working in September. I started my first job September 4, 2012, as a Senior Policy Analyst for the Department of Education.

Prior to here, I was first working at KPMG. When I finished my Masters Degree in Globalization Studies, I got an internship to work as a Municipal Management Intern for one year in the City of Kitchener. And after finishing that internship, I worked for KPMG. And then, from KPMG, that’s when I came here.

And let me just stress the KPMG part. I was working at Bay and Adelaide, which is at the heart of the financial district [in Toronto]. From there, I made the great journey to here. And people obviously were asking me, how are you able to move from the financial district of Toronto to here?

Well, it’s easy because what is here in Iqaluit is more or less like in Zimbabwe. So it wasn’t really much of a cultural shock, because it’s so much like I was coming home, away from home. I guess the only difference is the weather. But if I managed to move from Zimbabwe to Canada, I should be able to live anywhere else.

What are some of these similarities?

First of all, looking at the culture. You look at the way people relate to each other. We’re still more of a community, than individualistic. There’s still that strong sense of extended families, which is exactly the same thing [as Zimbabwe]. People still share, for instance, food. People go out, hunt, and come back and share. It’s a similar situation as back home. People still see that community spirit, where people can be able to look out for each other.

Volunteering at the soup kitchen Saturday evening. pic.twitter.com/aePhy1h7Os

— Kuthula Matshazi (@kmatshazi) November 23, 2015

And then if you look at infrastructure, or services – look at our internet. It’s expensive, it’s slow; same thing back home. It’s not something that we take for granted, like in Toronto. Look at the roads, you know? We don’t have perfect roads, we don’t have 21st century infrastructure, which is the same thing as back home. So that’s why I say, Iqaluit is the same as in Zimbabwe.

If I could just add one more issue – the legacy of colonialism. Zimbabwe is a former colony of the British, and here there’s a history of colonialism, so those two issues also, they make us more or less the same.

I think most people who know anything about, you know, the history of the world understand what colonialism was, and how it affected different regions differently. How specifically do you think that legacy of colonialism influences Nunavut and influences you in Nunavut?

I wouldn’t put too much emphasis on me, but I am just looking at the history of Inuit. From the residential schools, coming up to today, the building of communities, settler communities and so forth. I think those are the people that were much more affected by the legacy of colonialism per se, than myself. My context is in Zimbabwe.

I was born in a colonial Rhodesia and grew up in that. What I saw at that time and what we experienced at that time might be more or less what some of the legacy problems that I am seeing here. For instance, back home, when the British came, they uprooted families and put them in specific communities. And here also, there was also people who experienced the same thing. Relocation.

And then the issue of developing institutions and make them run under the Western kind of system, as opposed to the traditional or indigenous system. So those kind of things are the ones that have caused a disjoint from the original way people were living, and the way that people are living now. Right now, we have a problem with integrating Inuit societal values in some of the things that we do, because in some instances they might not gel together very well.

How do you compare the experience of being a Black man in the North and the South?

It’s difficult to compare. I think what I can say is, when you’re a Black man, consciously or subconsciously, you always have that thing, that you have to deal with who you are. You can’t just take it for granted that it doesn’t exist. That’s not true. It does exist.

We’ve seen a lot of strides that have been made in terms of trying to bring in laws that can help trying to bring equality to races. But still, those issues are still there. If you really put a microscope on some of the issues, processes. You know, the hiring processes, the differences in pay, differences in access to opportunities. Differences even, when you are engaging in public discourse. The way you engage in public discourse, it’s not the same as everybody else. Yes, your voices can be heard, but sometimes there is a time when it’s difficult for you to be able to be assertive and articulate your issues.

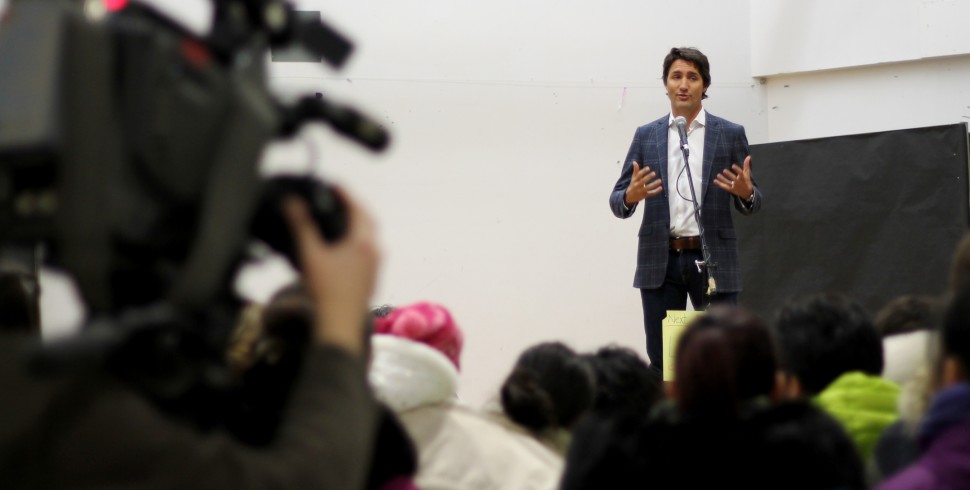

I guess what I’m trying to say is, is race is still an issue, whether it’s people doing it subconsciously or not, it is still an issue. But I think in the grand scheme of things, a lot of people have gone beyond it. And one example that I can just show is when I was elected as a councillor. Most of the people that elected me are not Black. I think we need to see that and really appreciate it that it’s a step forward.

Its official! I have been elected by the residents of Iqaluit as Councillor for the next three years. Qujannamik! Thank you! Merci!

— Kuthula Matshazi (@kmatshazi) October 20, 2015

I’m the first Black councillor and people actually went out to vote for me, which is really commendable. Even if you look at the corporate sector in other areas, Blacks have really made strides in getting into those areas. Blacks contribute extensive professional, trade, and entrepreneurial skills to Iqaluit and Nunavut. So there is progress that has really been made. But more still needs to be done.

You were talking about the difference in the way Black men sometimes engage in public discourse. Now, you’re a city councillor, so you’re now a local politician. Have you felt that pressure or that difference in the way that you engage in public discourse in Iqaluit, because that’s now your job?

Well, personally, I haven’t, and I don’t intend to. I’ll defend my space. But I wouldn’t want to speak for other people, who find some obstructions in terms of articulating their views or being able to be assertive in the public domain.

I think what I can say is, I think there are opportunities for people to engage in public discourse. It could be systemic, that you find difficulty in expressing issues, but personally, I haven’t experienced that. And if I do, I will assert myself.

So when you were elected, there were a few news pieces that were really focusing on “first Black city councillor.” How did you feel about that coverage?

At that time, when it was happening, lots of things that were happening. Like still trying to get to grips with, oh I’ve been elected councillor, and congratulations coming. And being somebody that has been in the community, I really didn’t see it as being the first Black councillor. I was just seeing it as an achievement, an individual achievement.

Top 5 news stories of 2015.

4. Nunavut elected its first Black City Councillor @kmatshazi #cndpoli pic.twitter.com/cVoUd8DdI2— wevotetoocanada (@Wevotetoocanada) December 31, 2015

But then in retrospect, I realize that, well, you know, there was much more significance to my election, than just Kuthula winning the election. I’m the first Black councillor, and most probably setting the pace and setting the expectations of many people.

But the media to its credit, I think they really gave me quite good coverage. It was really positive. I think it went as far as the United States and so forth, which was good. And I think it was very good for City of Iqaluit, in terms of when people think of Iqaluit, they just think that, well maybe Iqaluit is just composed of Inuit and there’s no Black persons and so forth. So I think it was really good for Iqaluit to be out there and having such positive publicity.

Tonight, meet Zimbabwe born @kmatshazi, Iqaluit's first black councillor@7:38pm https://t.co/MC6G1pTxXF pic.twitter.com/SJWTUdJjV3

— As It Happens (@cbcasithappens) October 26, 2015

Yeah. I haven’t looked at the exact numbers, but I’d be willing to bet that the Iqaluit city council is more diverse than the Toronto city council.

Oh yeah, absolutely. Yeah, it is. Let’s see, we’re eight. There’s one Black. There’s three Caucasians. There’s four Inuit. And Iqaluit has really embraced diversity. Our mayor is female.

What was your expectation before you moved up here about the diversity?

Well, I had an advantage because there was already somebody who was living here. He’s from Zimbabwe, he’s a friend of mine, so he really told me what Iqaluit was like. The diversity and so forth.

What I didn’t know was the level of telecommunications, because when I first came here, I tried to switch on my blackberry and it couldn’t work. Because we were still using those phones without SIM cards. But otherwise, when I was coming here, I knew exactly what I was coming to.

You’re also raising your daughter in Iqaluit. How do you try to get her in touch with her own heritage, while she’s growing up here?

Right from when she was young, that is what we’ve been working with her on understanding. For instance, all around her it was English, so she had to understand why we are the only speaking Ndebele, which is our language. So we conditioned her to understand that we are Ndebeles. And then we taught her that when she’s at home, it’s purely Ndebele, we don’t speak English at home. I mean, she thinks in English, because of where she was born, but every time we short circuit it.

And then the other thing that we did to help is to understand the issue of diversity. When you go out, you’re going to meet white, black, whatever colour. That’s okay. People are different. Even now, she’s so sophisticated. She now understands how to communicate. She knows that, this is Aunt Nuvusutu, she’s Ndebele. This one is Aunt Stephanie, she’s from Jamaica, she speaks English. This one is Anubha, she’s Bangladeshi, she speaks English. That’s how we’ve conditioned her.

Now when we went back home, last year, it sort of solidified her understanding of her culture and also her language skills. That was an opportunity for us – we went for six weeks – it was an opportunity for us to really drill it in her, that this where you come from, this is your heritage, these are your relatives, these are the expectations you as Ndebele, that you should be. But at the same time also she’s able to interact with all these different cultures and races.

You were living here for three years when you started running for council, and you know Iqaluit has its issues with newcomers and southerners and transients. So what motivated you to run for city council?

All my life I think I’ve been involved in public policy issues. And then when I came here, I started volunteering for the Economic Development Committee. And then it really gave me an opportunity to see all the huge challenges that were there. Coming from a municipal background in City of Kitchener, I saw there were so many challenges that needed to be dealt with and I wanted to help. To be part of the people who are going to participate in addressing the issues that I was seeing here.

With Minister Hunter Tootoo at NL2016. 1st time meeting him after our respective gruelling but successful campaigns. pic.twitter.com/XHx1j14ePx

— Kuthula Matshazi (@kmatshazi) January 31, 2016

For instance, lack of infrastructure. Like, until today, I still can’t understand why Iqaluit is so different from all other cities in the country. Why should we be scrambling for bare minimum? If we’re not like any other capital city, then at least we must be like some of the smaller cities. In terms of infrastructure, it’s really difficult to understand why we cannot have some basics or why we don’t have services or we have high food prices. I still don’t understand. I still don’t understand. Those are thing kind of things that really made me want to participate in public policy.

Were you ever worried that you wouldn’t be elected?

My approach was, if you’re going into an election, you’re either going to win or lose. That’s the attitude that I got. If I win, thats okay, if I lose that’s okay. But I think what I did was I did my part. Prepared myself very well. Tried to meet as many people as I possibly could. I expected anything to come, because you never take people for granted. So I was prepared for either way.

Diary of a Councillor within the next week! pic.twitter.com/yu5V7oevWB

— Kuthula Matshazi (@kmatshazi) November 24, 2015

But the people I was meeting, they were really open and they wanted to consider my message. When you are campaigning, it’s really difficult to really gauge how people are going to vote. But I did my part, walked everywhere I possibly could. And I left it up to the electorate to decide whether they would vote for me or not.

Anything else you’d like to add?

You touched on an interesting thing: transience. I’m here for a long-haul. So I really want to make Iqaluit my home. We’re not planning two, three years, or five years, or ten years. We probably could retire here. So Iqaluit is my home.

I’m hoping that by maybe five, ten years later it will be a completely different Iqaluit. Still driven by Inuit values, still appreciating the Inuit values, but at the same time, I hope I see a situation where people don’t go down south to go for holidays or to get some other services or products. They should be here. We shouldn’t be going to Ottawa or Montreal or other cities. We should also be competing with those cities for tourists, for everything else.

Imagine Iqaluit having a similarly buzzing downtown core! We would spend Iqaluit $$ here and grow the economy! pic.twitter.com/9F5AccYPAB

— Kuthula Matshazi (@kmatshazi) January 30, 2016

We just want to be like any other community. Not feeling pity for ourselves. I want us to experience that. And I want to be part of that change.