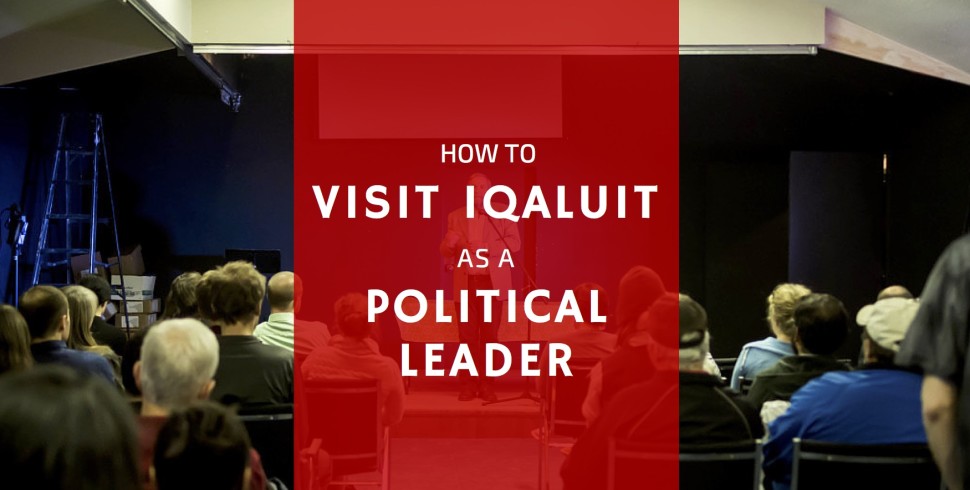

It’s Black History Month, and to celebrate this year, Finding True North presents “Being Black in Iqaluit,” a four-part interview series. Check back each Friday of February for future installments.

First, meet Nmesoma Nweze, a 17-year old student who grew up in Iqaluit – and she’s also the model for the Iqaluit Black History Month logo! It’s a long and worthwhile read, so let’s just get into it! Photos are embedded from Nmesoma’s Instagram account.

FTN: Tell us a little about yourself and your connection to Iqaluit.

Nmesoma: I was born in Nigeria, so I moved from Nigeria when I was two months, and my family first moved to Yellowknife, and then we moved from Yellowknife to Vancouver, where I spent my early childhood. We lived there from when I was like a year to five, and then my parents split up and we moved to first Cape Dorset, actually, when I was seven, and then we moved to Iqaluit when I was eight. I’ve been in the North most of my journey in Canada.

I grew up obviously as a minority, I guess, whatever that means. But I guess in a really unique type of situation that not a lot of Nigerians get to experience, growing up in Nunavut and in Iqaluit specifically. It’s a very, very different relationship with race that I’ve always had. I think if I had to describe myself, due to my background, growing up in Iqaluit, in one word, I think it would be dichotomy, because Iqaluit is home. It is home.

But the relationship I have with the term home isn’t one of ownership; it’s one of deep appreciation and love. And sort of almost owing. I don’t want to say duty, but one that comes from gratitude and love, that you want to contribute to that place. But you definitely – and I’m grateful for this – you know your place due to the fact that Nunavut belongs to the Inuit. That’s a fact, and that’s wonderful.

Growing up beside their culture and having all those of beautiful pieces rub off on me and forming the way I think, is great, but it was also a struggle. Growing up trying to find the perfect mix between where I grew up, and the culture that belongs to me, that I am so estranged from physically.

It’s weird, I’m still figuring out who I am in terms of that, but I think for me going into the future it’s going to be way more about taking ownership of what is mine. I’m trying to learn my language, Igbo, the language that my mom speaks and my family speaks, my entire family, and reclaiming the part of me that’s always been there. It’s just a dichotomy and it’s so weird, it’s such a weird mix. Arctic Africans, can you even believe it, you know? But it is. It is.

Do you remember that experience, moving from Vancouver to Cape Dorset?

I did my first communion the weekend before we moved, and I remember that really, really vividly. All those things we were cramming in before leaving. I remember that I was also learning to ride a bike at the time, and I had just gotten my training wheels off, and then I found out that hey we’re moving, and we couldn’t bring my bike with me. I’m re-learning how to ride the bike now.

I remember going to Costco and Walmart and just packing bags and those big containers full of stuff, and I was like, where are we going? Are we going off the grid or are we running away? And even the picture I have from my first communion, I look into the eyes of that child, and I look happy but I also look really kind of confused, and in the beautiful enlightened way that children look when they’re confused, like they’re about to embark on a new adventure.

Then we moved and it was really cold and I remember just seeing snow everywhere and I was like, okay this is cool. I lived in Vancouver so all I’d seen [was] rain and slush and I was like, this is a fun new way to live. The first place we went was to NorthMart. And me and my sister were too scared to get out of the car so we were like, hey mom we’re just gonna stay here. And we stayed in the car and her and her friend that came to pick us up from the airport went in to get a couple necessities.

And I love her A photo posted by HELLAcuddles (@yaaasdaddy) on

I remember it was scary because I’m like, six, my sister’s like four, and a whole bunch of little kids come from out of nowhere and start rocking the car. And I’m immediately like, I want to leave, I want to go back home, why are we here? We just start holding each other and wondering what’s going on, like what we got ourselves into. And I think that was my first encounter with the word Portagee. But like, I had no idea what that meant.

The kids rocking the car, saying Portagee. What do you think motivated that behaviour?

I think it was just like, yo, she’s a newcomer and let’s do this. Obviously, it wasn’t the kindest way to introduce yourself. But we were all kids and I think they just happened to look into the window and that’s what they saw. It was just something that they attributed to me. It definitely wasn’t malicious. It definitely wasn’t you know, trying to make a statement or anything or making us feel like we were unwelcome.

It’s just one of those memories that sticks with you, in hindsight. When I moved to Iqaluit, it was when I learned what that word meant. But that day, it was just a random vocab word. I have Dictionary.com on my phone and every morning it gives you a word of the day and it kind of reminds me of that. The word before you actually read the definition is just letters and sounds and jumbled up with no meaning.

I think that that’s why that memory sticks with me, because all it is, is just letters and sounds and motions and this new feeling of being in this new place with these new people and this new everything that has no meaning, that had no meaning at that point yet. So yeah, I don’t think it was racially motivated, it’s only in hindsight when all those symbols, all those signs in that scene now have meaning, do you realize that was very telling and that’s very formative, I guess, for me. But at the time, no. We were all just kids you know. Kids don’t know what’s going on.

So then you moved to Iqaluit. What was that transition like?

That was cool. That was really good. It just felt like a hand was going to be fit to a glove. We moved and it was different. It was bigger, but it also felt a good size. I think Iqaluit really fit us, and it does really fit us. But it was also a different again. I had to be indoctrinated into the social dynamics of little children and of an entire new city and a city that’s vibrant.

There’s a voice to Iqaluit. Iqaluit just has so many facets to explore. And I think it was overwhelming at first, an overwhelming process of just being indoctrinated to a new place with all these different possibilities, all of which were totally foreign to me, and a lot of which I didn’t know if were for me. I didn’t know if I was welcome in that sphere or what role I could take. So that’s still something that you gotta juggle. But it was good. Like I said, it just fit. It just fits.

Are you saying that you weren’t sure about how welcome you’d be to sometimes to things that were traditionally Inuit? That you weren’t sure if you should be taking on that kind of…

Yeah, and I mean, I, like most people, am not a fan of cultural appropriation. I love cultural appreciation. I love people who come into the location and they listen and they talk to you and they ask questions and they wear what they’re supposed to wear to be respectful and they do what they are supposed to do to be respectful. But I’m not a fan of walking in and deciding this is mine, this is cool, but you guys can keep that. You know, picking and choosing the parts of a culture you want to take on.

I know that with traditional Inuit culture, those are things that have been practiced for thousands of years. I have my own from home that have been practiced for thousands of years. And those things have been aggressively attacked by colonizers and governments and if they’re still there and they’re being maintained and nurtured and cultivated by the people – I guess I want to say I was always aware of the possibility of me quickly taking on an intrusive role in those things. And I erred on the side of caution due to that fact that I know I wouldn’t be that cool if someone came into my traditions.

At the time I was having a very large identity crisis in terms of, who am I? Where do I fit? But I knew that it’s not my place to declare that I fit [in Iqaluit]. It’s your place to appreciate and learn and love, but it’s not your place to decide that this is yours. So, I think that that’s where I was standing for a lot of my time and standing for my time at home. Because you’re aware, you love this place and you appreciate this place and you have a duty to improve this place, but don’t come in there like you’re the boss, you know?

How do you think being a Black woman has specifically influenced the way you view Inuit culture and life in Nunavut?

When you come from the perspective of a person of colour, not only are you kind of used to being the one who’s the not the most advantaged in the situation anyway, you also realize, I’m dealing with another culture that’s faced aggressive amounts of colonial influence,and they’ve survived. And they’re way smaller than my population from where I’m from!

You realize that we understand what it means for our cultures to be put on display and to be sideshow acts and touristy treats for dominant European cultures. And you’re like, I don’t want to do that, because I find that exhausting and annoying and not fun in general for me, when someone else is like, so oh my god, can you play like the drums? Can you beat your drums for me? Can you dance? Can I touch your hair?

I don’t like being on display, I don’t like being a caricature. I don’t feel like I need to put someone else, in their own town, in their own place, in their own territory, into the position of being that for me. Because no one likes that. You know?

Do you think you did find a sense of community in Iqaluit?

Yeah. End point, yes. Definitely. Like I said, Iqaluit is home. And the only reason I call it that is because I do have my community, my core group. People who respect me, and respect also themselves and their identity as Inuit or their identity as whatever they may be. But also mine as not [Inuit], but still as someone who loves and appreciates their home.

It was difficult at first because in Iqaluit, it can be broken down to two major themes of general mistrust of outsiders due to history, and then an ignorance. Just not knowing due to obviously the amount of [different] people that you’ve seen. No one can know about something that they’ve never seen. In terms of being a Black African in Iqaluit, the only Black Africans that the North has ever had, that the media has ever portrayed [are] really, really, really horrible stereotypes.

#nunavut A photo posted by HELLAcuddles (@yaaasdaddy) on

There was a lot of pioneering I had to do in my early years. Elementary school and early middle school, I was like, I am going to portray every stereotype I possibly can in order to be palatable. Almost like I was selling myself like a brand, like I was going to be the Black friend. That worked to an extent, but it also didn’t work because I felt like crap. It didn’t sit right. I wasn’t being who I was. And I also knew if it was working, it was working for the wrong reasons. I wasn’t showing people who I was. And the person that they were deciding to call their friend wasn’t genuine.

And I thought about it kind of long term. If I were to walk away from this place today, and the only image of a Black human being that some people had was the person that I’m showing them, the person that I already know is not me, would the next Black person to come here, would I make their life easier or harder? And I decided harder.

So then I decided, I already knew I’m not going to pretend in any way that I’m entitled to Inuit culture and I’m not going to wear that as some kind of badge. Like, oh my gosh I’ve lived here this long, now I’m one of you. I would hate that if someone did that to me. I do hate that when people do that to me! I already knew that I wasn’t going to go into that other extreme of just trying to blend. So I did have to be myself, and I did have to learn what that was, as every person growing up has to do.

But what I have to say is that I found my community, but I also had to create my community by speaking candidly about race and about relations and calling people out when they say something and calling people out when they want you to act like a stereotype. There’s a perfect balance between knowing your place but not being trampled on, and deciding that you also are entitled to having your voice, the voice that you own, in the choir of Iqaluit and the mosaic of that culture. So it was about knowing my place, but also defending that place, you know? And communicating that place and making that place as genuine as possible. You find it, but you also have to create it. You really do.

How did you connect with your Black heritage? How have you connected with being Black while living in a place where there’s not a lot of Black people?

That’s like my favourite, favourite thing to talk about. Honestly, seeking it out is pretty easy. I go home at night, I’m raised Nigerian. I’m raised in that tradition. I’m raised to be Nigerian Igbo, to be an Igbo women. That was great because then I had my mom right there and I had my family just a phone call away.

So it started at home but then I’m very lucky to be born at the time that I was born because through social media, I got to reach out to a lot of actually activists. Especially through Twitter and stuff. I have such a strong tie to who I am as a Nigerian and as an Igbo woman at home, but I also understand where I lie. I also understand growing up in North America and what it means to be Black in North America and the fact that I can walk into any place in the world in North America and say, hi I’m igbo and that means nothing because I am Black first before any of that.

And talking to other Black people and talking about racial issues and getting involved in that community, online and in person. Finding people in Iqaluit like Lekan, who are just so vocal and so talented and understand that dynamic. I just talked and talked and talked to people and sought people out and I found a really good place now. And I’m really looking into activism. I’m in contact with the Black Lives Matter chapter in Toronto. The Afro-Carib group at UBC is doing a week-long event, spoken word, and performances and different talks and panel discussions and we’re going to volunteer, a group of Afro-Caribs here.

And I think for me it was just reaching out and kind of not resolving, because I don’t see it as an issue, but kind of justifying and sorting out and putting the perfect puzzle together of who I am. And what it means to be Igbo, a woman, Black, North American, African, Nunavummiut. And all that together and understanding that I don’t fit very perfectly into one category, but realizing that I’m such a great part of so many brilliant categories. And putting them together and realizing, that’s really great. And you’re going to have a really great role in your life and in other people’s lives. Hopefully. I don’t want to assume that, but I hope that I’m doing okay. At least for my sister. I want to be a good example for her.

#throwback #loveher #sisters #homies A photo posted by HELLAcuddles (@yaaasdaddy) on

Pingback: SUNDAY LINKS | GUTS Canadian Feminist Magazine

Great story. Thanks for sharing it, Nmesoma.