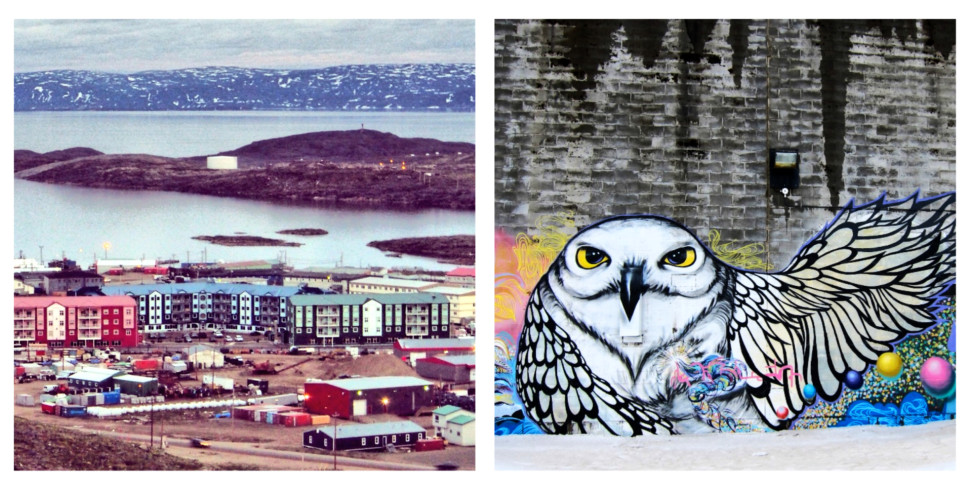

Without a doubt, the most common topic of conversation online and in person the last few weeks has been about A Tribe Called Red in Iqaluit. From desperate social media posts searching for tickets to one of their two sold-out shows (apparently pairs of tickets sold for up to $400; face value was $40-50), to amped up dance parties spinning only their latest release, Nation II Nation, the deejay trio’s performances were arguably the most anticipated events of the year.

The band was in Iqaluit (their first visit!) for the weekend, first to play at Toonik Tyme’s Big Band Night, and then for a set at the Legion. In between their shows, the members of A Tribe Called Red – Deejay NDN, Bear Witness, and Deejay 2oolman – sat down with us to talk about their creative process, why they think they’ve avoided backlash, and how they remain connected to their audience even as they grow.

You have two shows scheduled in Iqaluit, back-to-back nights, and they both sold out – I think the Legion show sold out in just days. How did that feel?

Deejay NDN: It’s super cool that we can go to a place that we’ve never been before and then sell it out. That’s incredible. To me it means more than winning any award or anything like that. These are people that are paying to see us. It’s not just some industry guy that thinks that our music is cool. It’s huge. We love Iqaluit for that. It’s awesome. We can’t wait to come back.

What do you think that signifies?

Bear Witness: That it was about time we played here. About damned time.

How would you compare your shows in Iqaluit and other tour locations to your ongoing Electric Pow Wows?

Deejay NDN: Whenever we play a festival set or we’re performing as A Tribe Called Red, we kind of have a set. When we’re playing the Electric Pow Wow, we’re playing for, like, three and a half hours or something like that, so it’s a lot more just free deejaying. We don’t have to be playing our festival set, which we can do in our sleep now. We get to actually be deejays, feel the crowd out, take them places.

Who do you think your music appeals to?

Bear: We have a really, really broad audience. Definitely don’t have one average listener at this point. I hear stories from all different age groups, people from everywhere. People seem to identify with [our music] on some level right across the board. I think it’s one of the things that’s helped this project a lot, being able to appeal to a lot more than just the electronic music audience.

What do you think it is that makes your music appealing to a broad range of people?

Deejay NDN: Maybe it has something to do with pow wow music, it having some sort of familiarity, but also not really hearing it like that before.

Bear: It’s different. It’s not something that has really been done in the way we do it.

The next album will be a collaborative venture. Are you planning to work with any Nunavut or Inuit musicians?

Bear: Yes.

Are you allowed to say who?

All: Uhhh…

Deejay NDN: It’s not too hard to figure it out if you think about it for awhile.

Bear: We’ll leave it there.

Okay, so forget the album then. Are there any other Nunavut musicians that you’d hypothetically like to work with?

Deejay NDN: Nelson Tagoona is a wicked kid, really talented. I can’t wait to see The Jerry Cans tonight because all I’ve been hearing about is how great they are. It’s going to be wicked.

A Tribe Called Red has won a Juno, been nominated for multiple Polaris Prizes, and your music, in particular Sisters, has radio and club play. What do you think the mainstreaming of your music means for Aboriginal music in Canada?

Deejay NDN: I don’t know if we’ve gone mainstream yet. Although we have won some mainstream awards and stuff which is pretty big. It’s huge for indigenous people. It’s the first time that that’s happened since the inception of the Aboriginal Award within the Junos. It’s kind of finally shattering that glass ceiling that a lot of indigenous artists had within Canada.

Other artists have received some criticism for taking indigenous music and making it mainstream. Are you surprised that you haven’t faced that backlash?

Deejay NDN: Very surprised.

Why are you surprised no one’s been critical of your work?

Deejay NDN: There’s been attempts at doing what we’re doing in the past, and they’ve been shot down really quickly by Elders and stuff. They weren’t using [traditional songs] respectfully. We know these songs have a life, it’s a life that’s within them, and that they can’t be disrespected like that. I think we hold it in a different respect than it was in the past. And it seems to resonate.

Bear: We’re lucky in that respect, because Tanya [Tagaq] is a really good friend and she’s always telling me, “You guys are so lucky” because [we] talk about being a voice for our community and talk about the support that we get from the community, from people saying to us that [they] want [us] to represent [them]. [Tagaq] gets a hard time from people, from her own community for what she does. You were given the example of people who have been disrespectful in the past, but somebody like her who isn’t [disrespectful] at all, but she does get that push back. And I think we’re just really fortunate that we don’t. I think we’re really confident that what we’re doing isn’t stepping over any lines and isn’t breaking any protocols, when we have drum groups who are willing to work with us and collaborate with us and create with us. We’re not just a group who takes prerecorded music and remixes it. We’re actually getting involved with the artists who are producing it.

Were you very conscious of all this when you started?

Bear: Extremely. As soon as we started sampling pow wow music, it was like, well what does this mean? How does that work? We know the protocols in pow wow. If you’re going to sing somebody else’s song, you’d better have learned that song from that person and that person better have given you permission to sing their song. So how does that translate when we want to sample somebody’s song? How do we approach those protocols, when we’re not singing somebody’s song, we’re taking something that’s already been put out there in the world and sampling it in the same way that funk or reggae or blues gets sampled into other music? How do we as indigenous people then have to reconcile with the protocols? And there were stumbling blocks along the way, you know. It wasn’t an easy process on any level. On our level, figuring out how to approach [the drum groups], on the drum groups level trying to figure out what we were doing and trying to feel us out, and in the middle you have record labels trying to do the business part. So you have all these layers of-

Deejay NDN: Messing up. [laughs]

Bear: But because we’re indigenous, we have this whole other layer on top of all that normal business stuff. We have a responsibility to our culture and the protocols and respecting all those things.

Deejay NDN: When we started, we were expecting push back for sure.

When you started Electric Pow Wow or when you started actually recording?

Deejay NDN: Sampling and putting out the pow wow mashups and stuff. We fully had conversations about how we’re probably going to get pushback, what should we say, how should we approach this. The only problem we’ve had was an Elder had mentioned that it was off-putting that we use the word pow wow where alcohol is served. And she followed it up really quickly with, “But I really like what you guys are doing.”

Bear: That’s the main criticism that we’ve gotten. Not that we’re remixing pow wow music, but that we’re presenting it in an environment where alcohol is being served. Which if you know pow wow culture at all, that’s a huge no-no, right. There’s been that question a lot but never to the point of-

Deejay NDN: You guys can’t do this anymore.

Bear: I think people see the value of what we’re doing because we’re reworking culture in a way that makes it not only interesting for youth, but interesting for people outside of our culture. You go back to what you were talking about who we appeal to. I don’t want to compare ourselves to anybody, but I was just thinking of a comparison in terms of culturally what’s happened, and you look at what Bob Marley did with reggae. He took music that represented a very small piece of the world and reworked it in a way that now reggae comes from everywhere in the world. And people identify with and know reggae all over the world. That’s because somebody took that culture and put it into a package that everybody else could identify with as well. In a sense we’ve done that, but we’ve also made that package for our own people.

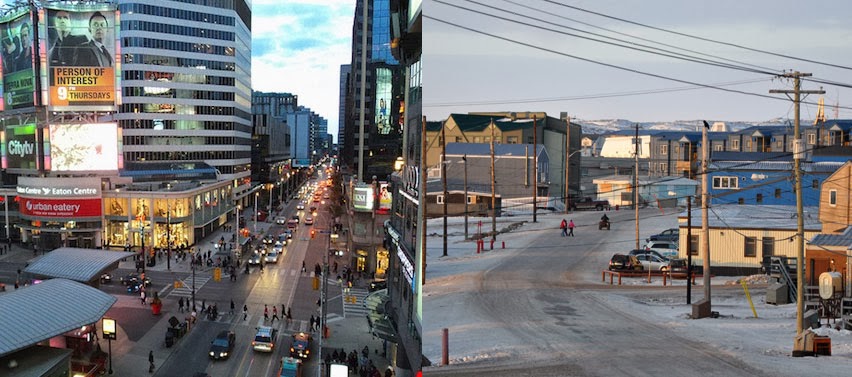

You started A Tribe Called Red to showcase Aboriginal music in your circles, for a mostly Aboriginal population. Now you’re playing at Coachella. With growth and success, how do you remain connected to your original fanbase?

Deejay NDN: We still play that party. We play it every month. To stay grounded. People say, “How do you go play Coachella?” Well, we still play that 200-seater club in Ottawa every month, just because it’s fun.

Bear: And the next show that we play after Coachella is Gathering of Nations. And after Gathering of Nations we go and play Tucson and Phoenix. All of those are going to be heavily indigenous in attendance. There’s a balance that we find, you know? Yeah, Coachella is our next show, but after this one [in Iqaluit]. I was thinking about that today. It’s something that we really made a conscious decision about in the group, that we had to remain accessible to the community that we’re making our music for. That we operate our business in a way that we’re not always making the best financial decisions, necessarily. We make the most conscious decisons, I guess, is the best way to put it. We do the things that we feel are right and we put that foward before anything else.

It seems like your growth is very organic, and not strategic or calculated.

Deejay NDN: We have a manager who is very focused on our career. There was a huge festival that we played in France and it was insane – there were five, six thousand people there. And I was like, “This is insane.” And he was like, “Remember that show I turned down two years ago? It was so that I could get you this now.” And I was like, “Two years ago? You made a move two years ago for us to be here right now?” He was that focused.

Bear: We have people who are making those calculated moves. But they’re really understanding and aware that when it comes down to it, if it’s something that we don’t feel comfortable with-

Deejay NDN: We won’t do it.

Bear: We’ll shut it down. We have an agent who does placements for commercials and films and stuff, so he’s always coming to us with these things. So he’s like, “Are the guys going to be okay with FIFA?” It’s like…

All: Nope.

Bear: [laughs] No, we can’t do FIFA.

Deejay NDN: There are these really weird placings for our music. There is a typeface that used points in the letters, so it didn’t use as much ink, and our song was used to advertise that. It was brilliant. It was perfect. There was nothing native about it. We were just accepted as being good music. Which was amazing.

Big thanks to Will Glenn for his help setting up this interview, as well as Tamara Fast for the amazing header photo featuring hoop dancer James Jones.

Think you know which Nunavut artist will be on A Tribe Called Red’s next album? Or did you get a chance to see A Tribe Called Red in Iqaluit? Let us know in the comments or on Twitter!